Current research projects:

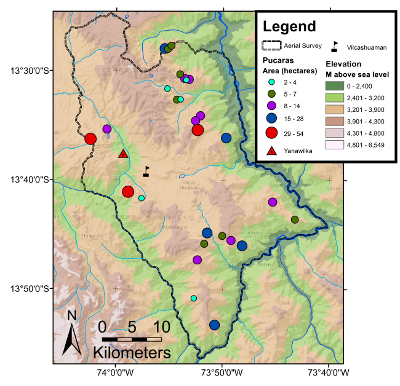

1. Title: Inka State Consolidation through the Remaking of Landscapes in Vilcashuamán province

Description: This five-year archaeological project investigates how Inka state consolidation, especially the resettlement policy of mitmaq, created new social landscapes in Vilcashuamán province, a geopolitically strategic area both before and after Inka conquest. The Inka reorganized the labor and social landscapes of their subjects on a scale and degree that was unprecedented in the Americas. In particular, the Inka mitmaq policy resettled a quarter to a third of the total subject population. The Inkas resettled the mitmaqkuna, people affected by the mitmaq policy, far from their homes to farm and craft for the Inka. According to the chroniclers, the mitmaq policy was the brainchild of the Inka emperor Pachakuti. Before the implementation of the mitmaq policy, people kept rising up in rebellion and reconquests were needed constantly. The Inka were intimately knowledgeable about the political geography of the subdued provinces: they measured, surveyed, and made clay models of the social, ritual, and physical landscapes in order to decide which hillforts to demolish, which inhabitants to relocate, which fertile lands to appropriate, and which sacred places to incorporate in their own image. Despite the mitmaq's centrality in Inka state consolidation, we know little about the mitmaqkuna outside of ethnohistorical sources written with Inka and Spanish state interests in mind. Archaeological investigation is thus needed to assess the social world of these peoples.

The Inka province of Vilcashuamán is an ideal setting to explore Inka state consolidation of social landscapes. After the Inkas conquered Vilcashuamán province with much difficulty, they implemented the first large-scale mitmaq program, under which they depopulated nearly the entire province and transplanted subjects from other parts of the empire to labor for the Inka. As of now, there has been little systematic archaeological research on how the Inkas remixed conquered landscapes. Because Vilcashuamán province was arguably the earliest example of the mitmaq program implemented on a large scale, and the provincial capital of Vilcashuamán was considered by the Inka as the geographic center of their empire, understanding how landscapes changed with the Inka conquest can give us a systematic understanding of the specific strategies of state consolidation. This project will also uncover narratives about how the people of Vilcashuamán province pushed back against Inka manipulations of social landscapes.

This five-year project compares the pre-Inka hillfort community of Pillucho to the nearby community of coerced transplanted laborers (mitmaqkuna) at Yanawilka, which was part of my dissertation research. It will investigate the changes in local flora (through environmental reconstruction via coring of sediments from the nearby lakes Pomacocha and Cochararacán), ritual landscapes, food landscapes, and economic exchange networks of goods such as obsidian. Pillucho was an important hillfort where the Inkas besieged the inhabitants for over two years. According to ethnohistorical documents, the inhabitants of Pillucho took refuge there from a wide area and from diverse ethnic groups, indicating some level of inter-ethnic political cooperation before the Inka conquest. The significance of this project is to provide an Andean example of a state program of “legibility,” as described by James Scott, where non-state spaces are transformed into controllable spaces through the reconfiguration of social and geographical landscapes.

2. Title: The world of Pablo Chalco: Folk magic and cosmopolitanism in the Tupac Amaru II rebellion

Description: I am working on a historical anthropological project on Pablo Chalco and his family, who were famous ritual specialists and leaders in the Tupac Amaru II rebellion in the Ayacucho region. Understanding how the common folk, who made up the bulk of the rebel forces, were able to put aside long-standing animosities that mapped onto class, caste, and ethnic lines is crucial to understanding why the rebellions were able quickly to spread through the Andes. Previous scholarship on the Tupac Amaru II rebellion has focused on the social world of the Cuzco region, where the rebellion began, but little has been systematically researched on the social conditions that led to the spread of the rebellion elsewhere. In the Ayacucho region, the Tupac Amaru movement was organized from the bottom-up. How was the Tupac Amaru II rebellion able to gain so much sympathy and support in the region of Ayacucho? In the Cuzco region, the supporters and detractors of the movement generally fell along long-standing lines of enmity between noble native families, but it remains a mystery why ordinary folk with no ties to noble families from Cuzco would join. In both regions, we do not have a good understanding of the folk religious practices and the leaders who mobilized the masses.

Through the lens of Pablo Chalco, his family, and his social world, we have an intriguing glimpse into the ritual aspects of rebellion and the central role of women. Chalco had a cosmopolitan life trajectory. According to a 1780 census, he was a forastero, or migrant, with access to the community lands of Chungui in the eastern highland jungles of Ayacucho. Chalco was originally from the province of Cuzco, but had settled in Chungui as a coca farmer, livestock raiser, and agriculturalist. Chalco had lived in Chungui with his mother since at least 1762 and had married a woman from Huamanga, not far from Chungui. The court case against the Chalco family accused them of various acts of idolatry and witchcraft. According to native witnesses, he frequently proclaimed in public, especially during festivals, that Tupac Amaru had been crowned king and ordered people not to pay tribute tax, and predicted that there would no longer be priests or magistrates. Petrona Canchari, his wife, and Maria Sisa, his mother, were accused of being witches. In the list of items confiscated from their house, there was a yellow bag with an array of ritual items inside. The items included sea shells, coca, bread, sweets, chili pepper, “various small stones in diverse figures,” rosary beads, and a “black stone made of volcanic rock shaped like a bone [of the Inca].” The court document presents the most detailed description of the relationship between rituals and the Tupac Amaru II rebellion that we currently have. Further research on Pablo Chalco and his social world should illuminate the ritual aspects of mass mobilization in the Tupac Amaru II rebellion, a topic that has been entirely absent in scholarly literature.

First, I will do further archival research on Pablo Chalco, the prison plantation and textile workshop to which he was condemned (Ninabamba), and what he did after his escape from prison. Second, using the detailed census documents of Chalco’s community and surrounding communities that I already collected during my dissertation research, I will analyze the social structure of those communities: marriage patterns, landholding patterns, the proportion who were migrants and where they came from, and the degrees of similarity between communities based on surnames using Lasker distance methods. Doing so will shed light on how cosmopolitan the communities were and what potential there was for interethnic cooperation or strife. Third, to judge whether the Chalco family’s ritual practices were part of a wider shared understanding among ordinary folk of various backgrounds, I will research the ritual practices and associated material paraphernalia of eighteenth century south-central Peru. Criminal cases related to witchcraft often contain inventories of the houses of the accused, providing insight into how ritual paraphernalia were used. By analyzing the material culture of ritual described in archival documents, this research project lends an archaeological framework to understanding social networks over the wider landscape in the late colonial Andes.

Past research projects:

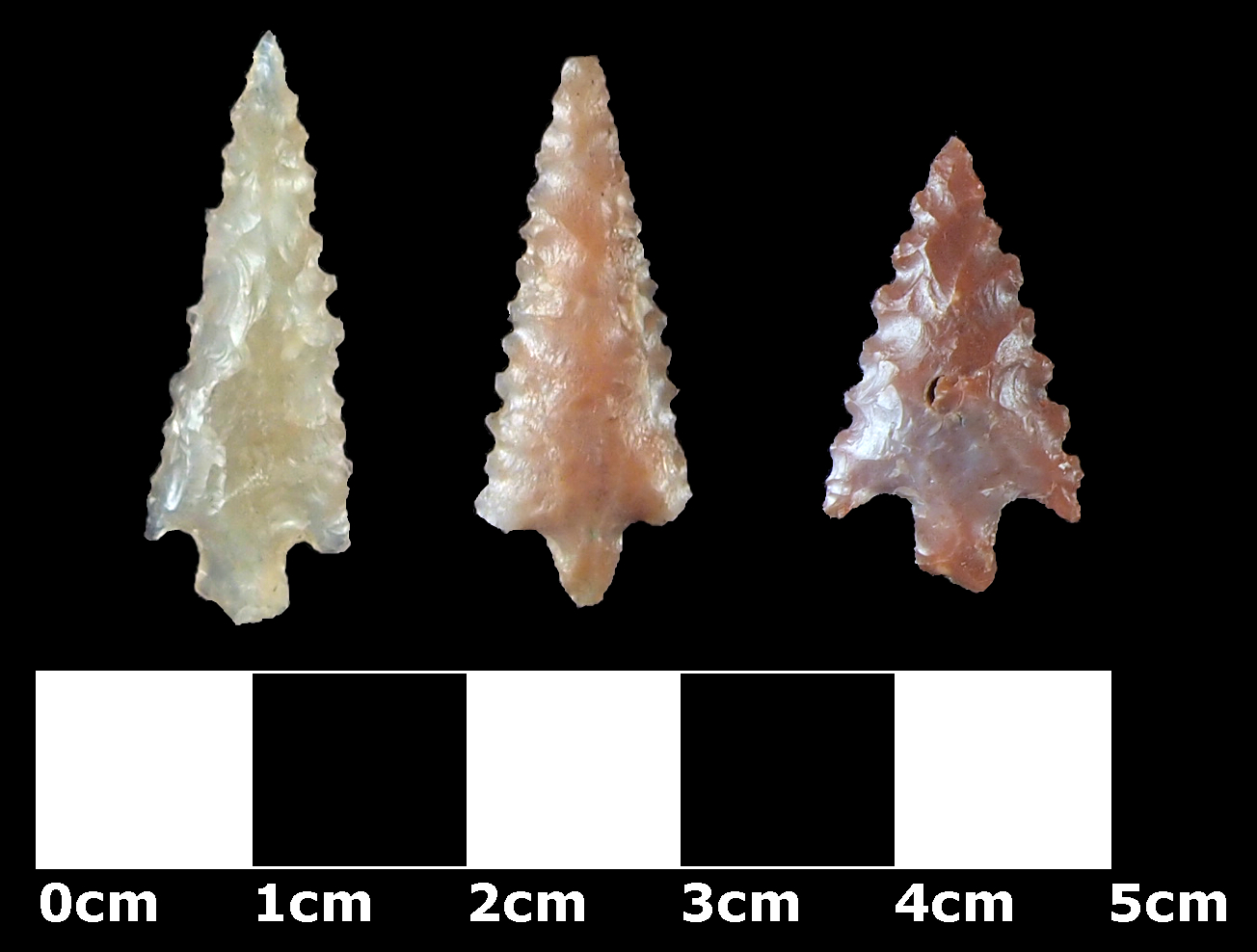

1. Title: War or Peace? Assessing the Rise of the Tiwanaku State Through Experimental Archaeology and Projectile Point Analysis

|

Examples of serrated Tiwanaku-style projectile points from the Taraco Archaeological Project. |

Collaborators: Christine Hastorf (UC Berkeley), Bruce Bradley (University of Exeter), Daniel Vera (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos), Karina Aranda (Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Vanessa Jimenez (Unidad de Arqueología y Museos).

Outputs: 1. Hu, Di. 2017. John Wymer Bursary Report: War or

peace? Assessing the rise of the Tiwanaku state through projectile-point analysis. Lithics 37: 84-86.

2. “War or peace? Assessing the rise of the Tiwanaku state through projectile point analysis.” with Christine Hastorf, Daniel Vera, Bruce Bradley, Karina

Aranda, and Vanessa Jimenez. Paper presented at WAC-8, Kyoto, Japan, September 1st, 2016 . Session on flaked stone analysis in South America

organized by Astolfo Araujo, Mercedes Okumura, and Bruce Bradley

2. Title: Labor under the Sun and the Son: Landscapes of Control and Resistance at Inka and Spanish Colonial Pomacocha, Ayacucho, Peru

Abstract: Why do the oppressed not rebel, especially when they outnumber their oppressors? What are the social conditions for armed rebellion? Should we be focusing on armed rebellion rather than other kinds of resistance? This dissertation examines these general questions about the nature of social movements in the context of Spanish colonialism. Specifically, it unpacks the long term social conditions that enabled the conjuncture of local armed revolts and regional-scale rebellions in the late colonial period (late eighteenth/early nineteenth century) in Peru through a combination of archaeological and historical evidence. The primary case study is a village called Pomacocha, located in Vilcashuamán province in the modern region of Ayacucho, Peru.

By putting an important case study “under the microscope,” we can examine how

local social conditions influenced regional social conditions for revolt and vice versa. Pomacocha was intensely affected by both Inka and Spanish colonialism and provides rare insight into the lives of the people whose labor sustained the colonial regimes. It began as a transplanted colony of agriculturalists (

mitmaqkuna

) to supply food for the nearby Inka palace and the Inka provincial capital of Vilcashuamán (Willka Wamán). After the Spanish conquest, the agricultural settlement at Pomacocha was abandoned. Later, an

hacienda

-

obraje

was established and a new native community sprang up around it. The area became a politically and economically important zone for the Spaniards. How did the materiality of social relations inform strategies of resistance by exploited laborers in the Andean village of Pomacocha? Historical documents attest to the poor working conditions and abuses at the textile workshop of Pomacocha during the Spanish colonial period, but no significant armed uprising occurred until after the Tupac Amaru II rebellion of 1781. To understand and contextualize the short-term and long-term causes of the late colonial upheaval, I analyze the long-term evolution of strategies of control and resistance at Pomacocha, starting with the Inka period. I combine archival research, archaeological excavations and surveys, analysis of material culture, surname analysis of censuses, and space syntax analysis to show that strategies of state control and bottom-up resistance coevolved from the Inka period, and that this coevolution resulted in a social landscape conducive to alliances across social groups in the late colonial period. There has been little archaeological work aimed at understanding the relationship between forms of resistance and the materiality of social relationships of coerced laborers in the Inka and Spanish colonial periods. By understanding the effect of Inka and Spanish colonial institutions of labor on identity and social cohesion, we gain a better understanding of the motivations, enabling social conditions, and strategies of resistance to such institutions. By taking a long-term view of how the workers of a single community negotiated strategies of control of labor, my dissertation fleshes out a typical case study of the interplay among local motivations and wider social context for general rebellion in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Outputs:

1. Hu, Di, and M. Steven Shackley. 2018. ED-XRF analysis of obsidian artifacts from Yanawilka, a settlement of transplanted laborers (mitmaqkuna), and implications for Inca imperialism. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 18: 213-221.

2. Hu, Di. 2017. The Revolutionary Power of Andean Folk Tales. Sapiens. May 16, 2017. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/andean-folk-tales-revolutionary-

power/

3. Hu, Di and Alicia Miranda Alcántara. 2016. Informe Final del Análisis de los Restos Arqueológicos Exportados del Proyecto de

Investigación de Pomacocha Colonial. Submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Lima, Peru.

4. Hu, Di. 2015. Engaging historical archaeology through fiction: A ‘choose your own adventure.’ https://performingthepastpresent.wordpress.com/chooseadventure/

5. Hu, Di. 2013.Stahl fund final report 2013: Archival research and balloon aerial photography of Pomacocha, a Late Horizon and Spanish Colonial

site, in Ayacucho, Peru.

6. Miranda Alcántara, Alicia and Di Hu. 2013. Informe final del Proyecto de Investigación Arqueológica de Pomacocha Colonial.

Submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Lima, Peru.

7. Hu, Di. 2012. Los documentos en el Archivo San Francisco de Lima sobre el obraje

de Pomacocha de las monjas de Santa Clara de Huamanga. Boletín del Archivo San Francisco de Lima 37: 3-4.

Presentations:

1. “Engaging historical archaeology through fiction: A ‘choose your own adventure.’” Society for American Archaeology Conference, Forum on “Performing the

Past/Present” organized by Bryan Cockrell, Katie Chiou, Marguerite DeLoney, and Di Hu, San Francisco, CA, April 16th, 2015.

2. “The evolution of control and resistance at an Andean textile workshop 18th-19th centuries.” Paper presented at the 2014 Conference for Ford Fellows, UC

Irvine, September 27th, 2014.

3. “Late colonial Andean revolts and rebellions: A view from the archaeology of labor and identity.” Paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology

conference, Quebec City, Canada, January 10th, 2014.

4. Changes in the materiality of language, landscape, and lithics in the Andes from the colonial era to the present.” Paper presented at the Society for

American Archaeology conference, Honolulu, HI, April, 2013.

5. “How do Slaves and Forced Laborers Rebel? Archaeology provides insight in two case studies from ancient Rome and the Spanish colonial Andes.” Public

lecture given at Berkeley Public Library, Berkeley, CA, January, 2013.

6. “Weaving for the Sun and the Son: A Comparison of Inka and Spanish Colonial Labor Organization of Textile Production.” Paper presented at the Society for

American Archaeology Conference, Sacramento, CA, March 2011. (Also presented at the Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga, November 24th, 2011 and at

the Fulbright Commission – Lima, Perú November 25th, 2011)

7. “Clothing and constraint: The history of control and resistance in the textile workshops of Ayacucho, Peru.” Paper presented at UC Berkeley, Archaeological

Research Facility November 17th, 2010.

8. Spanish Textile Workshops, Identity Transformation, and Revolts in colonial Ayacucho, Peru.” Paper presented at UC Berkeley, Archaeological Research

Facility September 23rd, 2009 and at Stanford University, Stanford Archaeology Center October 28th, 2009.

3. Title: The Lithics of Chiripa, Taraco Archaeological Project

Outputs:

1. Hu, Di, and M. Steven Shackley. 2018. ED-XRF analysis of obsidian artifacts from Yanawilka, a settlement of transplanted laborers (mitmaqkuna), and implications for Inca imperialism. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 18: 213-221.

2. Hu, Di. 2017. The Revolutionary Power of Andean Folk Tales. Sapiens. May 16, 2017. https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/andean-folk-tales-revolutionary-

power/

3. Hu, Di and Alicia Miranda Alcántara. 2016. Informe Final del Análisis de los Restos Arqueológicos Exportados del Proyecto de

Investigación de Pomacocha Colonial. Submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Lima, Peru.

4. Hu, Di. 2015. Engaging historical archaeology through fiction: A ‘choose your own adventure.’ https://performingthepastpresent.wordpress.com/chooseadventure/

5. Hu, Di. 2013.Stahl fund final report 2013: Archival research and balloon aerial photography of Pomacocha, a Late Horizon and Spanish Colonial

site, in Ayacucho, Peru.

6. Miranda Alcántara, Alicia and Di Hu. 2013. Informe final del Proyecto de Investigación Arqueológica de Pomacocha Colonial.

Submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Lima, Peru.

7. Hu, Di. 2012. Los documentos en el Archivo San Francisco de Lima sobre el obraje

de Pomacocha de las monjas de Santa Clara de Huamanga. Boletín del Archivo San Francisco de Lima 37: 3-4.

Presentations:

1. “Engaging historical archaeology through fiction: A ‘choose your own adventure.’” Society for American Archaeology Conference, Forum on “Performing the

Past/Present” organized by Bryan Cockrell, Katie Chiou, Marguerite DeLoney, and Di Hu, San Francisco, CA, April 16th, 2015.

2. “The evolution of control and resistance at an Andean textile workshop 18th-19th centuries.” Paper presented at the 2014 Conference for Ford Fellows, UC

Irvine, September 27th, 2014.

3. “Late colonial Andean revolts and rebellions: A view from the archaeology of labor and identity.” Paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology

conference, Quebec City, Canada, January 10th, 2014.

4. Changes in the materiality of language, landscape, and lithics in the Andes from the colonial era to the present.” Paper presented at the Society for

American Archaeology conference, Honolulu, HI, April, 2013.

5. “How do Slaves and Forced Laborers Rebel? Archaeology provides insight in two case studies from ancient Rome and the Spanish colonial Andes.” Public

lecture given at Berkeley Public Library, Berkeley, CA, January, 2013.

6. “Weaving for the Sun and the Son: A Comparison of Inka and Spanish Colonial Labor Organization of Textile Production.” Paper presented at the Society for

American Archaeology Conference, Sacramento, CA, March 2011. (Also presented at the Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga, November 24th, 2011 and at

the Fulbright Commission – Lima, Perú November 25th, 2011)

7. “Clothing and constraint: The history of control and resistance in the textile workshops of Ayacucho, Peru.” Paper presented at UC Berkeley, Archaeological

Research Facility November 17th, 2010.

8. Spanish Textile Workshops, Identity Transformation, and Revolts in colonial Ayacucho, Peru.” Paper presented at UC Berkeley, Archaeological Research

Facility September 23rd, 2009 and at Stanford University, Stanford Archaeology Center October 28th, 2009.

3. Title: The Lithics of Chiripa, Taraco Archaeological Project

|

Examples of flake tools from Chiripa (Taraco Archaeological Project). |

|

Calendar years |

S. Basin Phasing |

Basin Phasing |

Rowe Chronology |

|

1500-1000 BCE |

Early Chiripa |

Early Formative I |

Initial Period |

|

1000-800 BCE |

Middle Chiripa |

Early Formative II |

Early Horizon |

|

800-250 BCE |

Late Chiripa |

Middle Formative |

Early Horizon |

|

250 BCE- CE 300 |

Tiw. I Qalasasaya |

Late Formative I |

Early Intermediate |

|

CE 300-475 |

Tiw. III Qeya |

Late Formative II |

Early

Intermediate |

Table 1: Titicaca Basin Chronology (after Bandy 2004 and Hastorf 2008)

Through ceramic analysis and archaeological survey, others have shown that multi-community polities with their own stylistic and ceremonial traditions arose in the Middle Formative (Bandy 2004, 2006; Frye and Steadman 2001; Hastorf 2008; Steadman 1995, 1999). These important demographic and political transitions imply changes in the economy. This project analyzed the lithics of Chiripa to understand changes in procurement of raw materials and production during this important transition. The two main questions were:

1) Does the transition between the Early Formative and the Middle Formative reflect in significant changes in lithic production?

2) What artifact types co-occur and how do these relationships change over time?

A total of 1950 lithics excavated from dated and minimally disturbed contexts from the site of Chiripa were analyzed to address the questions. The lithics were excavated by the Taraco Archaeological Project from 1992 to 2006.

Most artifact classes showed significant changes that are consistent with increased nucleation of the different production stages as well as consumption and use of lithics. Ceremonially, Chiripa became an ever more important center for people to gather and celebrate in Middle Formative (Hastorf 2003; Hastorf et al. 2001). What is interesting is that the analysis of the Chiripa lithics suggests that the character of the gatherings may have also changed in Middle Formative. Because the nucleation of ceremonialism was an ongoing process since the Early Formative I, whereas nucleation of lithic production and use was most evident in the Middle Formative, it appears that the nucleation of ceremonialism actually preceded nucleation of productive activities like lithic production and agricultural production. This suggests that innovations in ceremonialism preceded innovations in the economy for the people who gathered at Chiripa, which is consistent with Hastorf’s (2003: 327) original thesis: “As the events grew more elaborate, they opened up the possibility to expand control in other realms, perhaps with ownership of lake resources, fields, or herds.” Ceremonialism preceding nucleation of productive activities may explain why we see monumental ceremonial architecture absent domestic and agricultural evidence elsewhere in the early Andes. A possible explanation is that as the gatherings became more regular, frequent, and involving more people, a critical tipping point was reached in both population size and level of cooperation, leading to innovations in lithic production.

Outputs:

Hu, Di. (Under review) The lithics of Chiripa: Implications for the increasing nucleation of productive activities on-site from the early to middle Formative. In: Recent Archaeology at Formative Chiripa: Production, Health and Intensification 1998-2006 Excavations of the Taraco Archaeological Project at Chiripa. Editor: Christine Hastorf.

4. Title: The Lithics of Kala Uyuni, Taraco Archaeological Project

Description:

|

Examples of flake tools from Kala Uyuni (Taraco Archaeological Project). |

This project focused on how the character of daily life changed from the Late Formative I to the Late Formative-Tiwanaku transition through the lens of lithics:

Generally, daily life through lithics did not change significantly over time at Kala Uyuni. Two notable exceptions, however, was the increasing production and/or use of quicklime and the presence of serrated edges on flake tools.

Outputs:

Hu, Di. 2010. Análisis de los artefactos líticos, In Excavaciones en Kala Uyuni:Informe de la Temporada 2009 del

Proyecto Arqueológico Taraco, pp. 102-122. Submitted to the Unidad Nacional de Arqueología de Bolivia.

5. Title: Chincha Material Culture from the Max Uhle Collection, Phoebe Hearst Museum

Description: This project examined scale beams and stone artifacts of the Chincha peoples of the Late Intermediate Period (1100-1476 A.D.) and the Late Horizon (1476-1532 A.D.). The collection of scale beams and stone artifacts of probable ritual function are housed in the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and was excavated by Max Uhle in September to December of 1900 in the Chincha valley of Peru. Kroeber and Strong’s (1924) monograph on Uhle’s Chincha collection skipped description of the stones entirely, so this project would fill in important gaps. This study represents the systematic analysis of the largest archaeological collection of Chincha balance beams and probable ritual stone artifacts.

Outputs:

Hu, Di. (Revise and resubmit) Changes in Chincha society accompanying Inka hegemony: Perspectives from the Uhle collection. Andean Past.